Why did Jeffrey Epstein cultivate famous scientists?

Last December, the U.S. Department of Justice released its first batch of files on disgraced financier and convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. Among the thousands of images was one video clip, the only one in the lot. It showed four seconds of the noted psychologist and writer Steven Pinker of Harvard University riding with Epstein on his now infamous private plane.

It wasn’t a great flight even in 2002, years before Epstein’s first criminal conviction, Pinker says of the trip, which was heading to a TED Talk. “I immediately disliked Epstein and thought he was a dilettante and a smartass,” he says. Pinker has not been accused of wrongdoing in connection with Epstein.

Epstein, who died in federal prison in 2019 while awaiting trial on sex trafficking charges, spent a lot of time talking to scientists. When more records are released from a reported stash of 5.2 million, now a month overdue, questions about what the “Epstein files” say about science and scientists are sure to arise. Already, e-mails dropped by a congressional committee and files released by the DOJ—thousands of notes, lists, videos and investigation records—have once again raised the question of why so many prominent scholars were involved with Epstein.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The financier widely courted pundits, politicians and billionaires, as the DOJ files confirm with photographs of everyone from Mick Jagger to Bill Clinton to Donald Trump appearing with him. (None are charged with wrongdoing in connection to the photographs.) A piano virtuoso, mysteriously wealthy and famously ingratiating, Epstein courted scientists for years, leading to investigations at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard, the results of which were made public in 2020. Last year’s e-mail releases revealed that astronomer Lawrence Krauss and linguist Noam Chomsky both associated with him long after his crimes became public knowledge. Last November Harvard launched a new investigation to look at connections between Epstein and economist Lawrence Summers, former president of the university.

Patronage

Money is one easy answer for why scientists were interested in Epstein. “Scientists need patronage; they need support,” says Bruce Lewenstein, a science communications expert at Cornell University. Wealthy patrons have funded scientists for centuries; they have paid for telescopes to investigate the atmospheres of alien worlds, brain mapping institutes, malaria prevention experiments, and much else. “That’s not good or bad; that’s what it is. And that has been true for 400 years,” Lewenstein says. Unlike many donors, Epstein usually wasn’t asking for his name on a building, and he donated money to everything from dance troupes to the Council on Foreign Relations, according to a 2019 Miami Herald report.

Before his 2008 conviction for soliciting minors for prostitution, Epstein donated more than $9 million to Harvard, including a $6.5-million gift to Harvard’s Program for Evolutionary Dynamics (PED), led by mathematician Martin Nowak. (Epstein continued to visit that program after his conviction—he did so more than 40 times in 2018 alone—and kept an office there.) He was also a Visiting Fellow at the university in the 2005–2006 academic year, after making a $200,000 gift to its psychology department. Following his conviction, donors he introduced to Harvard scientists gave $9.5 million to the school.

Then there were Epstein’s donations to M.I.T.: he donated $525,000 to the MIT Media Lab and $225,000 to mechanical engineering professor Seth Lloyd. Both gifts came after his 2008 conviction and were handled outside normal channels, according to a university report. Epstein claimed to also have arranged another $7 million in donations from billionaires Bill Gates and Leon Black to the school (Gates denied this, and the university report says there’s no evidence of an effort to “launder” Epstein’s money in the donations).

“The only generalization is that scientists, like the universities they work for, together with artists and others in nonprofit ventures that depend on philanthropy, routinely cozy up to wealthy people willing to slosh money around,” Pinker says. “Very few of these donors are heinous psychopaths, and he exploited their gullibility.”

According to Pinker, his pre-TED Talk flight with Epstein came at the behest of his literary agent, John Brockman, whose Edge Foundation also threw salons for Epstein that BuzzFeed News described as an “exclusive intellectual boys club.” (Brockman and his organization did not respond to a request for comment, and no reports of wrongdoing attended the events.) Epstein funded that foundation, which threw parties for billionaires and made contacts with people such as Pinker for him. Those contacts paid off: despite his dislike for Epstein, Pinker unwittingly contributed to the financier’s legal defense. Pinker wrote a 2007 opinion on the semantics of the wording of a prostitution law as a favor for Harvard professor Alan Dershowitz, who was Epstein’s lawyer and had once taught a course with Pinker. Pinker has said he didn’t know the opinion was for Epstein’s defense.

“I was doing a professional courtesy to a colleague—it’s routine,” Pinker says. “If I knew at the time what we know now, I would not have agreed.”

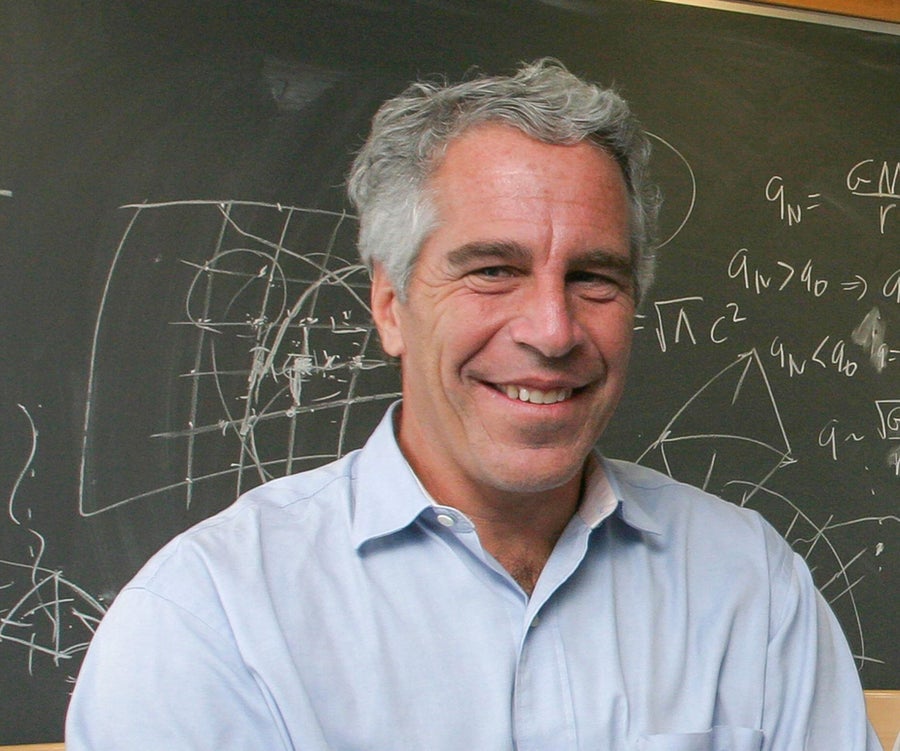

Epstein in a Harvard classroom in September 2004.

Celebrity

So, legal opinions aside, what did Epstein want from science? The simplest explanation is that Epstein collected prominent people. His financial networking relied on creating an aura of wealth and influence to entice investors. He was a “people collector” who traded information and favors, said Barry Levine, one of his biographers, in a 2025 BBC report. Scientists might have just been one of many influential groups he cultivated at a time that was “a cultural high-water mark for scientists as celebrities,” says Declan Fahy, an associate professor of science communication at Dublin City University in Ireland and author of The New Celebrity Scientists. Scientists wrote best-selling books, appeared in Vanity Fair and Vogue and gave viral TED Talks that were elevated online. “They moved into the power elite,” Fahy says, and so made sense for Epstein to cultivate.

According to Ghislaine Maxwell, Epstein’s former girlfriend and majordomo, who was convicted in 2021 of sex trafficking, conspiracy and transportation of a minor for illegal sexual activity, Epstein was particularly fascinated by brain science. In a July 2025 interview Maxwell told the DOJ that connections she had made through her father, Robert Maxwell, founder of scientific publisher Pergamon Press, led to her introducing Epstein to the Santa Fe Institute, a home to many high-profile scientists. (Epstein donated $25,000 to the institute in 2010.) “Epstein would have dinners at the house that I was tasked to organize and the scientists were a very major component of that,” she said, according to the DOJ transcript.

The scientist and writer Evgeny Morozov attributed Epstein’s scientific connections to Brockman—the literary agent who, according to Pinker, talked the psychologist onto Epstein’s plane—in a 2019 article in the New Republic. Himself a former Brockman client, Morozov recounted the agent’s attempts to connect him to Epstein and his “billionaires’ dinners,” whose attendees often were TED Talk speakers—invitations that Morozov declined.

The Edge Foundation was ubiquitous in science writing circles from 1998 to 2018, annually publishing books on scientific topics. It was also connected to the physicist Lawrence Krauss, a former member of Scientific American’s board of advisers, who was removed following sexual misconduct allegations in 2018. Released e-mail records show that Krauss asked Epstein for advice on handling those charges. Krauss has denied the misconduct allegations against him; none of the communications cited allege wrongdoing in connection with Epstein. (In 2014 Epstein was even invited to two Scientific American editorial meetings, which he did not attend.) Public records suggest the Edge Foundation received $638,000 from Epstein from 2001 to 2015, making him its major funder.

Social Prosthetics

One disturbing explanation for Epstein’s support of science comes from his interest in genetic determinism. This idea, which dates to the eugenics era, is still fashionable in some wealthy circles and can be seen in companies now offering designer baby services for embryos of would-be parents. In 2019 the New York Times reported that Epstein had ambitions of founding a “baby ranch” to raise children of women he impregnated (not unlike “secret compound” plans reportedly shared by SpaceX and Tesla chief Elon Musk).

“Given this stance, it is particularly disturbing that he focused his largesse on research on the genetic basis of human behavior,” wrote Naomi Oreskes, a historian of science, in Scientific American in 2020. “Scientists might claim that Epstein’s money in no way caused them to lower their standards, but we have broad evidence that the interests of funders often influence the work done.” (Regarding Epstein, Oreskes now adds, “The continued press attention reminds us that—rightly or wrongly—we are judged by the company we keep, and some money is tainted.”)

Perhaps the only direct evidence of Epstein’s scientific ambitions comes from a proposal he made in 2005 to be a Visiting Fellow at Harvard. “I wish to study the reasons behind group behavior, such as ‘social prosthetic systems,’” he wrote in an application proposing magnetic resonance imaging studies on human volunteers. “That is, other people can act as ‘prosthetics’ insofar as they augment our cognitive abilities and help us to regulate our emotions—and thereby essentially serve as extensions of ourselves,” he added, with a scientific gloss neatly encapsulating his view of humanity’s role in his life. Harvard approved him twice for the fellowship, though a 2020 investigation later noted his utter lack of qualifications.

A Rocky Pedestal

One last question is why anyone is surprised that celebrity scientists fell into Epstein’s orbit—as opposed to, say, rock stars or politicians doing so—in a culture driven by the worship of wealth and celebrity.

“A bit of this is [because] we have created an idealized picture of scientists that doesn’t match reality,” Lewenstein says. Scientists themselves like being seen as experts with their status on a pedestal, he adds. “They are very reluctant to acknowledge the social forces that shape their science,” Lewenstein says.

In other words, money talks in science. For decades, pharmaceutical-industry-funded research, for example, has more often reported favorable results in medicine. And money can control what science projects don’t get done; social media companies such as Facebook and X (formerly Twitter) have shut out researchers from examining their data—a vast, barely regulated experiment on billions of people linked to worse mental health in children. At the National Institutes of Health right now, in a very different era for science than one of celebrity, Trump administration political appointees are approving or disapproving allocations of the agency’s $48-billion budget for investigations judged as worthy by actual scientists, overturning the post–World War II standards for funding research.

Most of the scientists supported by Epstein weren’t overtly political and supported a once-uncontroversial view of science as an engine of progress, Fahy says. Things are different now, “where public debate around science in the U.S.—particularly around climate and vaccination—has become sharper, divisive, intensely political,” he adds.

All that leaves Pinker unsure why his four seconds on the plane in 2002 was the only video in the Epstein files to be initially released by the Trump administration. One reason might be to generate news stories such as this one about scientists, he says. “The more that journalists write about other people in photos, the less attention Trump’s entanglement gets,” Pinker says.