NASA readies for Artemis II mission, AI-powered speech gives stroke patients hope, and researchers discover oldest cave art ever

Kendra Pierre-Louis: For Scientific American’s Science Quickly, I’m Kendra Pierre-Louis, in for Rachel Feltman. You’re listening to our weekly science news roundup.

First, we have an update on humans going back to the moon.

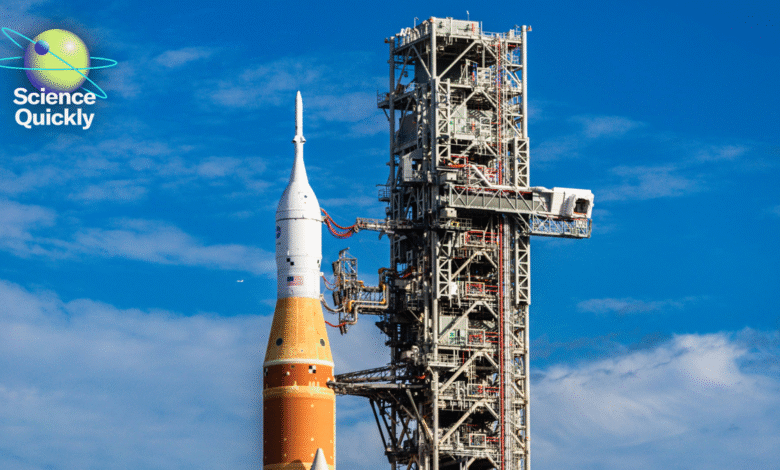

In the coming weeks the first launch window will open for NASA’s Artemis II mission. The planned lunar flyby will be the first crewed mission to go beyond low-Earth orbit since Apollo 17 in 1972.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

To learn more about it we chatted with Lee Billings, SciAm’s senior desk editor for physical science. Here he is.

Lee Billings: Artemis is NASA’s mission to send astronauts back to the moon. It’s been in development in various forms, under various guises, for 20 years now. Artemis II is really where the rubber meets the road. There was, obviously, Artemis I, but Artemis I was uncrewed—there were no astronauts on board. It was just meant to show that the key hardware components work properly, that they can get into space and go to the moon and come back. And now we are doing that with humans on board, so it’s much higher stakes.

Artemis II is not going to land on the moon. It’s not even going to orbit the moon. Some people get confused about that. It’s going to be on what’s called a free-return trajectory, which means it’s going to use the moon’s gravity to loop around our natural satellite and then send the Orion capsule, the Orion spacecraft, back to Earth at very high speeds. And so that means there will be some interesting spaceflight records being broken. One would be that the crew of Artemis II will be the farthest humans from Earth ever. They’ll also be the fastest humans in history ’cause when they return and they hit the atmosphere of the Earth, they’re gonna be going about 25,000 miles per hour, quite fast, and let’s hope that heat shield holds up.

In terms of things that it’s going to be studying, it’s a mix of a lot of human studies and space-medicine studies. The four astronauts that will be on board this mission, looping around the moon, will be instrumented and sensored all up. They’ll have all kinds of biometrics coming off them. And we’ll be doing that to have a better idea of how humans respond to the deep-space environment for notional future missions that will go to the surface of the moon, with Artemis III and onwards.

And, and so where we are now with Artemis II is that on January 17 it rolled out, in this very prestigious and ceremonial proceeding, rolled out from the Vehicle Assembly Building, this giant building that NASA has at Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida. And it was loaded on this giant diesel-electric tractor, essentially, to slowly, glacially go at about a pace of a mile an hour or so, from, the Vehicle Assembly Building to the actual launch pad where it will launch from.

The next big step is going to be something called the “wet dress rehearsal”; this is slated for February 2. And what that is, is when they pump cryogenic propellant fuel into the rocket so that they can see that it’s able to withstand all the pressures of all that fuel going in, making sure there’s no leaks or anything like that. And hopefully, we won’t see any leaks because if we do see a bunch of leaks, then it’ll probably delay what is supposed to be the onset of the launch window, which is February 6. And each month there’s about five days that the moon and the Earth are aligned so that, you know, we can pull this launch off, so if they miss that kind of five-day window in early February, well, we’re looking to March.

And why do we wanna go back to the moon? Well, a big part of it is geopolitics. We are no longer in this world of, like, the Cold War and the kind of golden age of the space race. It’s a new way now. There’s more players. India wants to go to the moon. China is going to the moon. And a big question now is whether or not we can beat them back to the moon, even though we already did it more than 50 years ago.

There are extremely interesting scientific questions as well. For instance, the places that people wanna go on the moon for this new generation of missions, it’s largely concentrated around the lunar south pole, which is where we know there are deposits of water ice and other types of volatiles. This is a very special region that has near-constant illumination from the sun but also permanently shadowed craters. And that region of the moon also is important because it could tell us a lot about how the moon formed and its history and evolution over time.

And finally, a lot of the, the south pole and the regions of interest are actually on the lunar farside, the part that people don’t see from Earth, and that’s important because you can build various types of facilities there to do cutting-edge science, such as a giant radio telescope to peer back to, essentially, the beginning of time. And you can do that there and be totally shielded from the Earth-based radio interference you would otherwise receive that would scuttle all your measurements.

Pierre-Louis: For more on NASA’s lunar mission go to ScientificAmerican.com.

Coming back to Earth a team led by University of Cambridge researchers may have found a way to give some patients their voice back after having a stroke. The key, researchers say, is a new device called Revoice.

You see, roughly half of all patients who experience a stroke also develop dysarthria, which weakens the muscles used for speech and breath control. The condition can cause slurred, slow or strained speech. It’s not that the patient doesn’t know what they want to say; it’s that they struggle to say it.

The good news is that with rehabilitation many patients regain their speech, but the process can take anywhere from months to years. Given that recovery is possible for patients, the scientists behind the new study wanted to help patients communicate faster than existing technologies that require letter-by-letter input.

The Revoice device the scientists developed consists of a soft collar embedded with sensors that track throat movement and heart rate and provide that information to two AI agents. Both of these agents process the data using a large language model. One of the agents reconstructs words from silently mouthed speech and vibrations in the throat. The other then expands those words into full sentences by using the wearer’s pulse to analyze their emotional state and detecting broader ambient conditions, including the weather and time of day. Combined, the system can anticipate what the person is trying to say and, with just two nods of their head, speak for them.

There are some limitations to the research: the study, published last Monday in the journal Nature Communications, had a small sample size of just five patients. But the researchers plan on expanding the study to a clinical trial. If the results hold, Revoice could be a useful tool not only for stroke patients but also for those with other neurological conditions, including Parkinson’s disease.

In other news about communication a study published on Wednesday in the journal Nature reveals the oldest cave art reportedly ever found. Previously, the oldest-known cave art were depictions of a pig and three humanlike figures thought to be over 51,000 years old. That art was found on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi.

This new discovery was found on the same island but in a different cave. Ordinarily, it’s hard to date cave paintings. But the limestone caves of Sulawesi are easier to work with. In fact the cave had been previously studied, but the new painting—a hand stencil on the ceiling—was overlooked. A chemical analysis found that the stencil dated back some 67,800 years at least, making it roughly 15,000 years older than the previously discovered cave art.

This discovery could help us pinpoint when humans first settled in Australia. Archaeologists suspect that humans migrated there through Indonesia but have been unable to determine the exact time frame.

Franco Viviani, a physical anthropologist who was not involved in the new study, told SciAm that the findings also offer new insight into ancient societies, saying, quote, “They confirm what is known today: that art is positively correlated to critical thinking and creative problem-solving skills.”

And speaking of creative problem solvers a new study on bats sheds some light on how these winged mammals get around. Every school-age kid at some point learns that bats are able to navigate in darkness using echolocation—that is, they send out a call and based on how the sound bounces back they can tell where an object is. But scientists have long wondered how bats navigate in object-rich environments.

A single bat call will send back echoes ricocheting off multiple objects from various directions and distances. In complex situations scientists figured it wasn’t really possible for a bat to analyze each individual echo, so they must be relying on an alternative strategy. Finding out exactly how bats might be navigating these kinds of environments was the focus of a study published Wednesday in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

To study this the research team constructed what they called a “bat accelerator” machine lined with 8,000 movable acoustic reflectors, or fake leaves. The goal was to mimic the experience of a bat flying through a hedge covered in real leaves. Over the course of three nights 104 pipistrelle bats went through the full eight meters, or roughly 26 feet, of the test track.

The results suggested that bats are sensitive to the Doppler shift, the same phenomena you experience when an ambulance siren shifts in pitch as it drives past you. According to the study, by paying attention to sound changes based on their own movement the bats are able to assess their surroundings and control their speed. The researchers say their findings could be useful in advancing drone technology in the future.

That’s all for today’s episode. Tune in on Wednesday, when we’ll dig into the nascent science of what foods make people stink.

But before you go we’d like to ask you for help for a future episode—it’s about kissing. Tell us about your most memorable kiss. What made it special? How did it feel? Record a voice memo on your phone or computer, and send it over to ScienceQuickly@sciam.com. Be sure to include your name and where you’re from.

Science Quickly is produced by me, Kendra Pierre-Louis, along with Fonda Mwangi, Sushmita Pathak and Jeff DelViscio. This episode was edited by Alex Sugiura. Shayna Posses and Aaron Shattuck fact-check our show. Our theme music was composed by Dominic Smith. Subscribe to Scientific American for more up-to-date and in-depth science news.

For Scientific American, this is Kendra Pierre-Louis. Have a great week!