Satellite Megaconstellations Are Now Threatening Telescopes in Space

Satellites Swarming Low-Earth Orbit Threaten Space Telescopes

Proliferating satellites are beginning to harm the science work of the beloved Hubble Space Telescope and other observatories

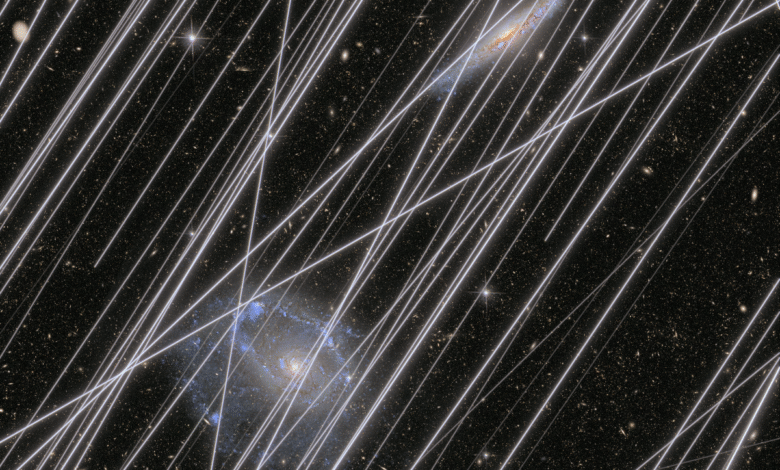

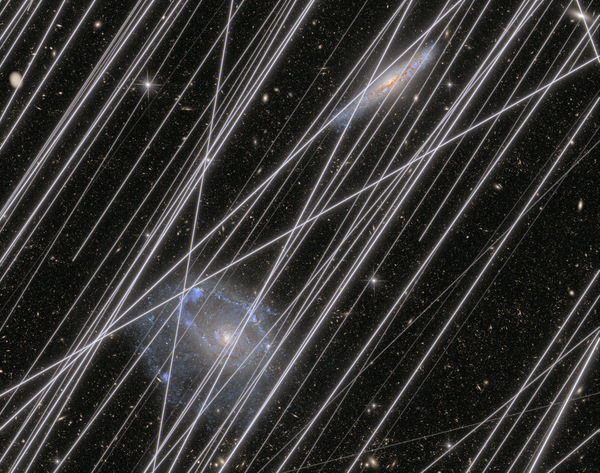

A simulated image represents the projected contamination by satellite trails in observations by the forthcoming Analysis of Resolved Remnants of Accreted Galaxies as a Key Instrument for Halo Surveys (ARRAKIHS) telescope.

NASA/“Satellite Megaconstellations Will Threaten Space-Based Astronomy,” by Alejandro S. Borlaff et al., in Nature. Published online December 3, 2025 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Today the globe is circled by thousands of active satellites—each prone to photobombing astronomers’ telescopes as an artificial star zipping across the night sky. Scientists working with ground-based observatories such as the cutting-edge Vera C. Rubin Observatory have long worried about this visual interference—but as satellites continue to proliferate, space-based telescopes, including the beloved Hubble Space Telescope, are beginning to suffer, too.

And the problem is only going to get worse. If companies follow through on their stated launch plans, Earth’s orbit will be home to some 560,000 satellites by the end of the 2030s. Many of these will be members of megaconstellations—groups of hundreds or thousands of satellites that all operate toward some common purpose, such as providing global broadband Internet from orbit. And according to new estimates published on December 3 in Nature, at least one satellite from such swarms could appear in one out of every three images captured by Hubble. Other observatories that the researchers analyzed will see traces of these satellites in nearly every individual exposure.

There’s no hard line at which satellite interference makes science impossible, but the light pollution created by megaconstellations is already showing up in astronomy data and distracting people who are trying to investigate the mysteries of the cosmos, says Alejandro Borlaff, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California and a co-author of the new research. “It will only get worse and worse and worse if we don’t find a solution,” he says.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

That much is obvious, but Borlaff and his colleagues went deeper. They gathered details about the thousands of satellites that companies plan to launch, including information about the spacecraft themselves and their orbits.

Then the researchers modeled how these satellites would appear to two currently operating space telescopes—Hubble and NASA’s recently launched Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer (SPHEREx). They also examined how the satellites would affect the observations of two planned space telescopes—China’s Xuntian observatory, which is scheduled to launch about a year from now, and the European Space Agency’s Analysis of Resolved Remnants of Accreted Galaxies as a Key Instrument for Halo Surveys (ARRAKIHS) mission, which could launch next decade.

All four observatories are very different, leading to different vulnerabilities to satellite interference. Xuntian must orbit quite low, for example, because it’s designed to be deployed and upgraded by astronauts from China’s Tiangong space station; this relatively low altitude means it experiences the largest number of satellites passing between it and the cosmos. SPHEREx has the lowest resolution of the four, so each individual satellite affects more of its images. SPHEREx also sees in infrared light, which satellites can reflect even when an observatory is augmented to reduce their optical visibility. Overall, the analysis found that the Chinese and European missions will be most affected by megaconstellations, with dozens of streaks appearing in every exposure if 560,000 active satellites are in orbit.

(The James Webb Space Telescope and NASA’s next major observatory, the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, are both safe from such orbital interference—both operate nearly one million miles away from Earth, in the direction opposite to that of the sun.)

Even for telescopes closer to home, NASA is more sanguine about the challenges megaconstellations pose. For Hubble, an agency spokesperson characterizes streaks in current images as “faint” and notes that although the number of satellite trails will increase, “most of these streaks are readily detected and removed using standard data reduction techniques.” For SPHEREx, the telescope’s operations require that its science targets be viewed repeatedly over time, which reduces the likelihood of satellites interfering with any individual observation of any given object, the spokesperson notes.

Even so, ever since the first launch of SpaceX’s Starlink megaconstellation in 2019, astronomers have been speaking out about the impacts of bright satellites on their hard-earned observations, especially ones made from ground-based telescopes.

“Astronomers in every area of astronomy have been experiencing gradually degrading observing conditions due to satellite streaks,” says Samantha Lawler, an astronomer at the University of Regina in Saskatchewan.

Ironically, one common suggestion has been to simply give up on ground-based observing and instead rely entirely on space-based telescopes—despite the expense and the near impossibility of upgrading them. “There are many reasons why that’s not a helpful suggestion, but this [study] really quantifies it,” Lawler says.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.