New Interstellar Object Comet 3I/Atlas—What We Know So Far as It Zips through the Solar System

New Interstellar Object Stuns Scientists as It Zooms through Solar System

All eyes are on Comet 3I/Atlas as astronomers worldwide chase the exotic ice ball through our solar system

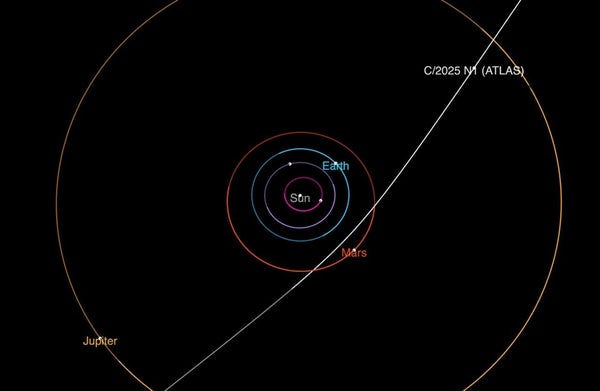

A diagram shows the trajectory of interstellar Comet 3I/ATLAS as it passes through the solar system. It will make its closest approach to the sun in October.

Late in the evening on July 1, a telescope in Chile that is part of the global, NASA-funded Asteroid Terrestrial-Impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) picked up on a new moving dot in the sky, an object traveling past the orbit of Jupiter. When Larry Denneau, a software engineer at ATLAS, alerted the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center to the observation, “it looked like a completely routine discovery,” he says. That would soon change. To his surprise, the object—provisionally named A11pI3Z—turned out to be the third interstellar visitor known to science.

Now, mere days after its discovery, frenzied follow-up work by astronomers around the world to further scrutinize A11pI3Z and look for additional apparitions in archival observations has given the object a new, more official name—Comet 3I/Atlas—for the telescope that first discovered it. What seems to have been the clinching evidence for its interstellar nature emerged from the efforts of a group of amateur astronomers, called the Deep Random Survey, who were the first to track the object down in images other ATLAS telescopes had captured in late June.

“We had quite a bit of confusion from the get-go,” says Sam Deen, a member of the group. “Our systems are usually tuned to expect that a new discovery is an object firmly stuck inside the solar system,” but Atlas was playing outside of those rules. The earlier observations—which soon also included “prediscovery” sightings from the Zwicky Transient Facility at the Palomar Observatory in San Diego County, California, as well as other telescopes—allowed a more precise calculation of 3I/Atlas’s trajectory. Whatever it was, the object was zooming toward the inner solar system at almost 70 kilometers per second.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

That’s “far faster than any solar system object should be able to move,” Deen notes, because such speeds ensure objects will slip through the sun’s gravitational grasp. Anything moving so quickly simply can’t hang around long; rather than following a typical parabolic orbit, 3I/Atlas’s blistering speed is carving out a hyperbolic orbit, a path that takes the object swooping through the inner solar system before it soars back to the interstellar void. It most likely came from the outskirts of some other planetary system, where it was ejected from its tenuous twirling around some alien sun by gravitational interactions with a giant planet or another passing star. Exactly where it came from and when it began its galactic journey, however, no one can say.

There is no threat to Earth: during its brief sojourn in the solar system 3I/Atlas is projected to come no nearer than about 240 million kilometers from our planet. The object will make its closest approach to the sun on October 30, reaching a distance of about 210 million kilometers, just within the orbit of Mars. As it approaches in coming months, astronomers will intensify their studies, hoping to learn more about this mysterious visitor.

What’s already relatively clear, however, is 3I/Atlas’s cometary nature; more than 100 observations have now trickled in from telescopes around the globe, including some that show hints the object is enveloped in a cloud of gas and dust and trailing a tail of debris as ices on its surface warm in the sun’s radiance. Astronomers normally use a distant object’s brightness as a proxy for its size, with brighter objects tending to be bigger as well. But a comet’s ejected material is usually bright, too, which interferes with such crude estimates.

Consequently, “right now we really don’t know how big it is; it could be anywhere from five to 50 kilometers in diameter,” Denneau says. Closer looks with more powerful observatories, including the keen-eyed, infrared James Webb Space Telescope, should soon help clarify 3I/Atlas’s dimensions and composition.

“I am interested in whether the comet looks like objects from our own solar system,” Denneau says. “The answer is interesting either way. If it has the same composition as a normal comet, it means that other solar systems may be built similarly to ours. If it’s completely different, then we might wonder why that is.”

The first interstellar object observed, 1I/‘Oumuamua, appeared on the scene in 2017 and perplexed researchers with its oddly elongated shape and bizarrely accelerating trajectory. Those strange features led some researchers to propose an idea—now convincingly debunked—that ‘Oumuamua was a derelict alien spacecraft adrift in the Milky Way. Then, in 2019, came the second observed interstellar object, 2I/Borisov, which bore all the hallmarks of a run-of-the-mill comet and thus inspired few, if any, outlandish claims of alien involvement.

“[ATLAS] will be a tiebreaker of sorts,” says Mario Jurić, an astronomer at the University of Washington and discovery software lead at the recently completed Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile. “[Will it] give us a sense ‘Oumuamua was the odd one out, or is the universe a lot more interesting than we imagined?”

Rubin—a unique telescope with a panoramic view that will survey the entire overhead sky every few days—is seen as especially critical for solving the lingering mysteries of these first emissaries from interstellar space. As the observatory’s survey progresses in months and years to come, it should uncover many more visitors from the great beyond, allowing astronomers to begin studying them as a population rather than scattered, isolated one-offs.

Ultimately, if Rubin or another facility manages to spot an interstellar object fortuitously poised to pass relatively close to Earth, astronomers might even be able to gain an extremely close-up view via a spacecraft rendezvous. The European Space Agency (ESA) already has such a mission in the works, in fact—Comet Interceptor, a sentinel spacecraft set to launch as early as 2029 to await some inbound destination. “There is a small chance that Comet Interceptor might be able to visit an interstellar object if one is found on the right trajectory, and the new Vera C. Rubin Observatory should give us an increased rate of discovery of these objects,” says Colin Snodgrass, an astronomer at the University of Edinburgh, who is part of the ESA mission.

All of that has astronomers on the edge of their seat, eager to dive deeper into a new frontier in our cosmic understanding. “This is probably the most excited I’ve been about any astronomical discovery in years,” Deen says.