Two Möbius Strips Combine to Create a Bizarre Object That Only Exists in 4D

Two Möbius Strips Combine to Create a Bizarre Object That Only Exists in 4D

In geometry, there are surfaces that do without an inside or outside—and some need at least four dimensions to exist

LAGUNA DESIGN/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY/Getty Images

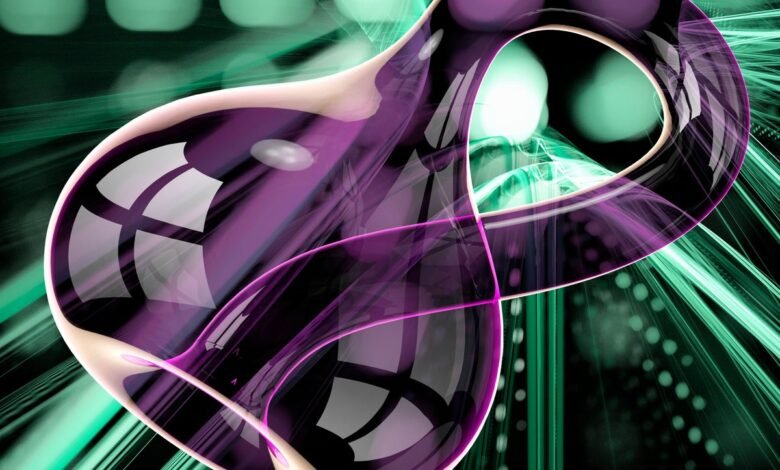

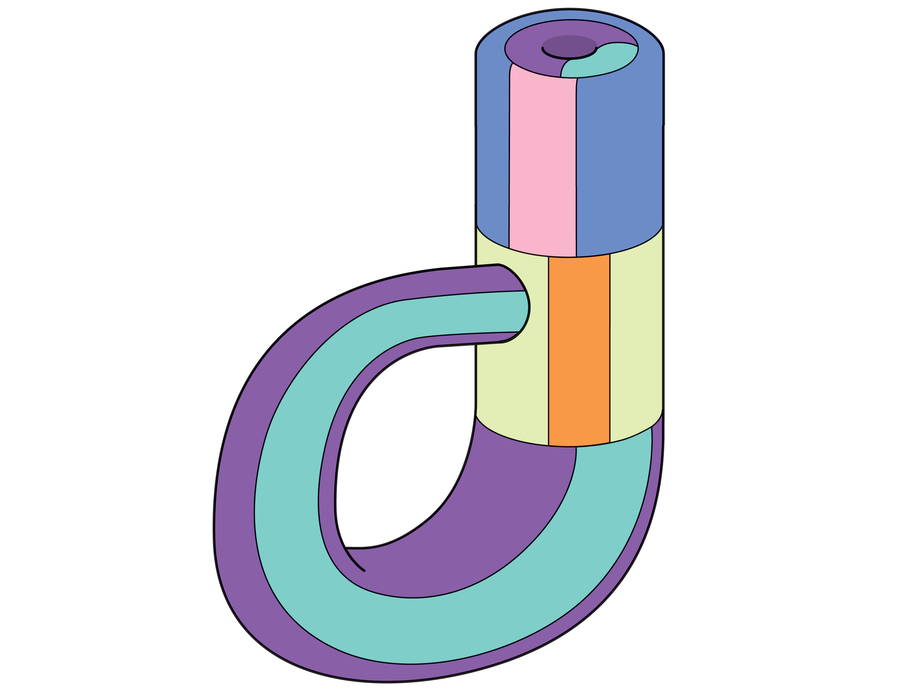

Visually, the “Klein bottle” doesn’t seem all that impressive. On first glance it looks like a trendy Japandi-style vase. And yet it has fascinated mathematicians for more than 140 years.

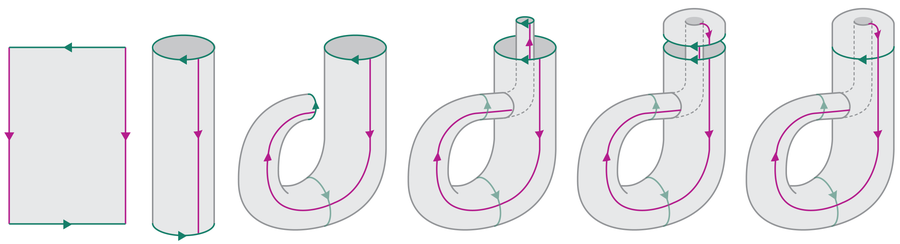

To understand why, we have to travel far back to the ancient Roman Empire, where the first traces of a somewhat simpler geometric shape can be found: the Möbius strip. This enigmatic shape is incredibly easy to make: Take a long strip of paper and bring both ends together. But before you glue the ends to each other, rotate one by 180 degrees. The result is a twisted band.

From a mathematical perspective, Möbius strips are fascinating because they have only one surface and one edge. Unlike a cylindrical object (such as one created by gluing together the ends of a strip that hasn’t been twisted), there is no inside or outside. For physicists, these twisted shapes make for excellent points of comparison when contemplating the properties of subatomic particles, such as the spin of the electron, which must be rotated by 720 degrees to get back to its start. And in factories, Möbius strips have been used as conveyor belts because they wear out significantly more slowly than untwisted belts, for which only one side is stressed.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

You can touch every point of a Möbius strip by running your finger along the shape’s surface without lifting it. Mathematicians refer to this as a “nonorientable” surface. If you enjoy hands-on experiments, I highly recommend trying to cut a Möbius strip lengthwise in different ways—the results are astonishing.

The German mathematician Felix Klein was also fascinated by the possibilities of these strange surfaces. He reasoned that if you glued two ordinary strips together along their respective edges, you could get a wider strip—that is, one edge of each strip would disappear. But a Möbius strip only has a single edge. So what happens if you glue two Möbius strips together? In this case, a surface without a border results. This strange creation is the Klein bottle, a surface that, like a Möbius strip, has neither an inside nor an outside.

Combining Möbius Strips

Now, if you’re getting ready to start taping together strips of paper to put this idea into action, I’m afraid I have to disappoint you. A true Klein bottle can only be created in four spatial dimensions. Yes, there are bottles inspired by the Klein bottle that exist in three dimensions, but they are technically just artifacts of the true Klein bottle in four dimensions. That’s because, when you embed this figure in 3D space, the bottle will invariably intersect itself, an obstacle that does not arise when you shape it in 4D space.

That said, we can at least try to visualize the Klein bottle. Imagine gluing the right and left edges of a piece of paper together, forming an ordinary cylinder. Then you glue the top and bottom edges together. But first, as with the Möbius strip, you twist them by 180 degrees.

Like the Möbius strip, the Klein bottle also possesses fascinating mathematical properties. Among other things, it represents the only exception to the Ringel-Youngs theorem, which deals with the coloring of objects. For example, if you want to draw a map and color the individual countries without neighboring countries having the same color, you only need four different colors—regardless of how the countries are arranged.

More generally, the Ringel-Youngs four-color theorem states the maximum number of colors needed to color countries on surfaces of different shapes. As it turns out, this depends on the number of holes in the surfaces. For example, I might decide to create a map for a doughnut-shaped planet. What is the maximum number of colors I would need in that case? Because the planet has one hole, it follows from the theorem that, at most, seven colors will suffice.

The Ringel-Youngs theorem applies to all surfaces except the Klein bottle. According to the theorem, the Klein bottle should only be colorable with a maximum of seven colors; as it turns out, however, six colors are always sufficient for the small bottle.

Because of such unique properties—and its nonorientability—the Klein bottle is one of several popular and mind-bending objects among mathematicians. It also appears in physics, where it can help describe complex quantum states, much as the Möbius strip illustrates spin states.

If you have any nerdy friends, the 3D Klein bottle—though not quite the real deal—could be a great Christmas present. You can even use it as a vase or wine decanter.

This article originally appeared in Spektrum der Wissenschaft and was reproduced with permission.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.