Earth’s core may contain 45 oceans’ worth of hydrogen

Earth’s core may contain 45 oceans’ worth of hydrogen

An experiment to quantify the amount of the universe’s lightest element in Earth’s core suggests that the planet’s water has mostly been here since the beginning

Earth’s core may contain up to 45 oceans’ worth of hydrogen, a new study finds—an estimate that suggests that the planet formed from a gas-and-dust disk that was rich in the universe’s lightest element.

The new research, published today in Nature Communications, also suggests that Earth’s water has been with the planet since it formed rather than having been delivered later by impacts from comets and other icy bodies. “It really changes the way we think of where our water comes from,” says Hilke Schlichting, a professor of Earth, planetary and space science at the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the research.

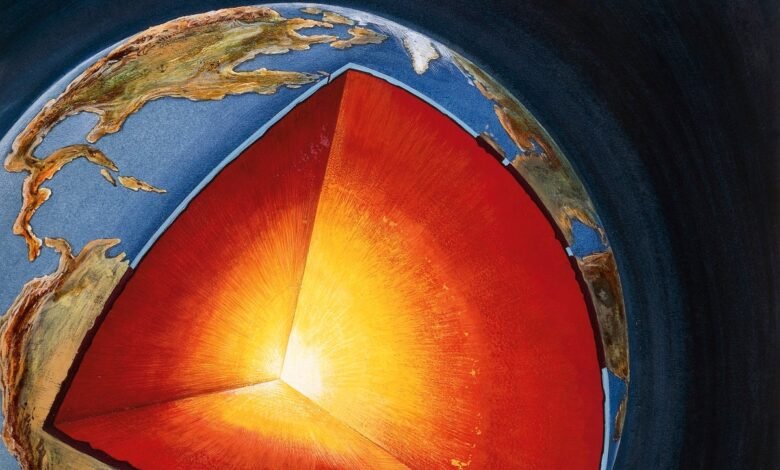

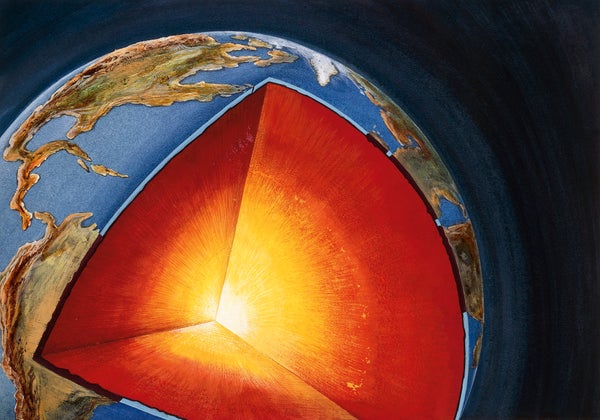

Earth’s core is mostly made of iron, but it’s not quite dense enough to be entirely composed of that element. Teasing out what percentages of lighter elements make up the core can reveal a lot about how the planet formed. But the core is too distant to measure directly, so researchers have to rely on computer simulations and high-temperature laboratory experiments that squeeze tiny amounts of various elements in diamond anvil cells under the temperatures and pressures of the center of Earth.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Hydrogen is a slippery element in these experiments, however, because it is so light and diffuses easily, says Anat Shahar, a planetary scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C., who was not involved in the new research.

In the new study, Dongyang Huang, a professor of Earth and space sciences at Peking University in China, and his colleagues found a way to pin down hydrogen. They pinched tiny samples of iron (representing the core) and hydrous silicate glass (representing Earth’s early magma ocean) between diamond anvils, heated the samples to about 4,827 degrees Celsius (about 8,720 degrees Fahrenheit) and squeezed them to pressures of 111 gigapascals.

The team then whittled down these already minuscule samples into needles with a point of only about 20 nanometers and bombarded the needles with a focused ion beam to peel off atoms one by one for analysis. The results revealed how silicon, oxygen and hydrogen stick together within iron when a planet like Earth forms. These ratios allowed Huang and his colleagues to extrapolate the amount of hydrogen present in the core; they estimate the element represents between 0.07 and 0.36 percent of the core by weight. That translates to the equivalent amount of hydrogen in nine to 45 oceans’ worth of water.

This amount of hydrogen in the core could only have arisen during the initial formation of Earth, says Schlichting, who adds that work from her group and others is now pointing to that same conclusion. That means the water cycle played a role on our planet ever since the core started cooling and hydrogen, silicon and oxygen started crystalizing inside it approximately 4.5 billion years ago, Huang says.

This crystallization, he says, would have created convection in the core, providing a “driving force for an ancient geodynamo to generate Earth’s magnetic field, which is indispensable for developing the Earth into a habitable place.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.