‘For ones who were there’: A new photo book charts the origins of DFA Records

Tim Soter’s new book of photography, “DFA Records: The Early Years,” opens with a shot from 2003, less than two years after James Murphy, Tim Goldsworthy and Jonathan Galkin founded the now-iconic indie dance label.

The spread captures Goldsworthy and Murphy posing uncomfortably in DFA’s wood-paneled studio, like two awkward boys at a school dance, a mini disco ball dangling between them. Murphy’s T-shirt reads, “Death From Above” — the label’s original name before the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center made it unusable.

Tim Goldsworthy and James Murphy at Plantain Studios, 2003 (Tim Soter)

The book, which Soter published under his own imprint “The Ship Escaped,” ends in 2007, with a photograph of Murphy running past the camera holding a bottle of wine, a nod, Soter says, to the musician and producer’s future Michelin-starred wine bar in Williamsburg.

What happened in between — the portraits, parties, candids, gear, private Hotmail correspondences, studios and live shows from DFA bands like The Rapture, The Juan MacLean, Black Dice, and, of course, LCD Soundsystem — is documented across 146 photos from Soter’s personal archive.

Whether you were there at the start, careening your way up to the stage at Bowery Ballroom, or celebrating DFA’s 20th anniversary last March at the Knockdown Center, (or both), Soter says he crafted this book with the fan in mind, intending to provide a raw viewpoint of what came first.

In this interview, Brooklyn Magazine speaks with Soter about the origins of DFA Records, what it means to compile a fan book and how the bands Soter captured were forged in a dark and uncertain time.

This interview has been edited for concision and clarity.

What inspired you to put this book together?

Just before the pandemic, I got an email from this guy who said, “Hey, I’m a photo editor and I’m pulling video and photos for this documentary called ‘Meet Me in the Bathroom.’” He told me he’d seen a few photos I’d taken of James [Murphy] and wondered if I had any other photos from the early days of DFA. I found photos I’d taken of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Interpol, Grizzly Bear, Animal Collective etc., and when I got to the DFA Records material, I began pulling it for the documentary. Then I realized, like, oh man, there’s enough material to tell a whole story, and I love making books.

How did you link up with them in the first place?

The book starts off with an email I found from a still-active Hotmail account from back then. There’s the exact pitch I sent to Jonathan Galkin, who was the label manager for 20 years. It’s me saying, “Hey, I want to be the guy that comes and takes all of the definitive portraits and press photos of the bands.” And the answer was like, “Yeah, okay, come on by.”

Why DFA?

It was my first Rolling Stone assignment. They sent me to shoot a College Music Journal show featuring The Rapture and De La Sol — an interesting combo! I photographed The Rapture backstage. That’s how I got DFA label manager Jonathan Galkin’s email. I also snagged some of DFA’s brightly colored monochromatic promo CDs. I liked the aesthetic and got familiar with more of the bands. In a funny way, I felt like I was backing the right horse at the time. I thought, there’s a lot coming together here and I want to get in while it’s all starting.

So after rediscovering these photos after 20 years, how do you go about organizing them?

I wanted to make the kind of fan book I loved as a high school student. I used to drive 45 minutes to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where Lehigh University is, where I found a book called “Joy Division + New Order.” It was put out by this tiny press in the U.K. called Omnibus Press, and it was great. It had a discography of all the bands — records and 12-inches. It had photos of the bands and their studios, anecdotes and technical stuff about how the music was made. This book was a dream to me; it had all the stuff I wanted to know about these bands but could never find.

How does this book emulate that fan book experience?

My photos are compiled for people like me — fans — who were actually there during the time period when DFA was coming up. It’s also for people who got into DFA, or, let’s say LCD Soundsystem, later on. They can look at these photographs and be like, holy cow, look at how young they were, look at what the gear was like, or what the offices used to look like.

Were there any local venues and/or DFA bands that you especially loved to shoot?

I had one really good live shooting experience with LCD Soundsystem at Bowery Ballroom. I was able to shoot the soundcheck which was interesting because the house lights were up so I could take different types of photos as opposed to when the band’s sweaty and performing for real. I’ve got a shot from the back, as LCD’s wrapping up the show and James has his hands in the air. You can see the entire venue in the photo, which shows this now-massive band performing for only 300 people on the floor. Simon Le Bon also showed up in the green room that night. I think he was trying to pitch them on producing the next Duran Duran album.

You shot so many shows for DFA and so many more for Rolling Stone. What was your main objective when capturing a live band?

I’m always trying to get one photo that embodies what the show felt like. Something that sums up the energy of a particular show. That’s the kind of game I play as a photographer: trying to sum it all up in just one frame.

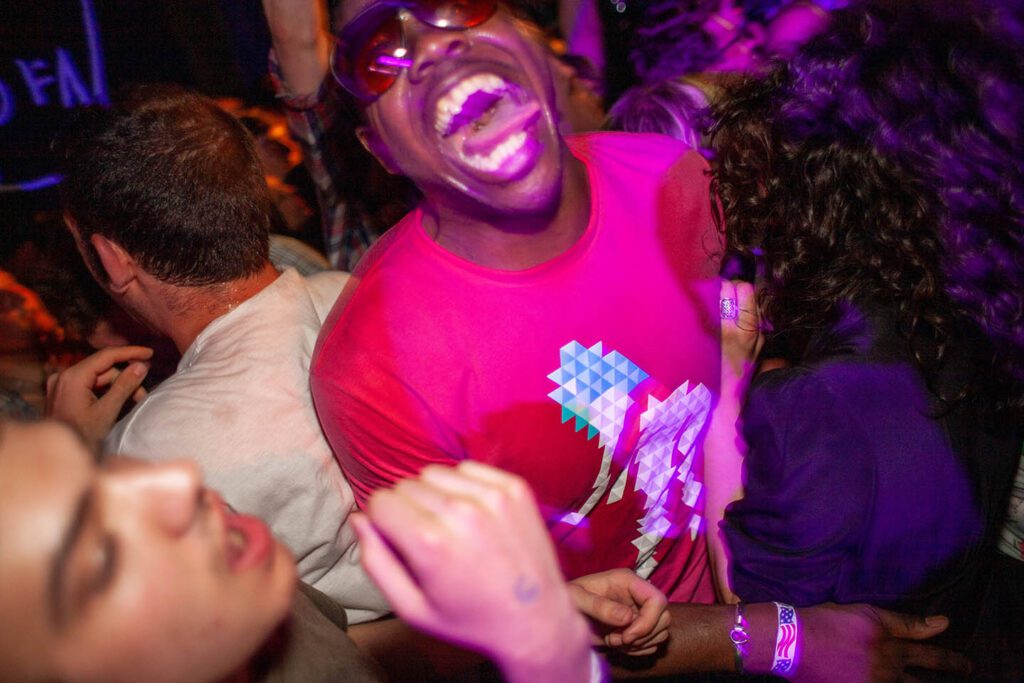

Fans, LCD Soundsystem at Studio B (259 Banker street) May 12, 2007 (Tim Soter)

How has your perception of the DFA photos you took shifted or changed over the years?

It’s cool to be able to go back to your 20-years-ago self and have all this material that you can now form into a story. I’m happy that I decided to document all the gear at DFA’s studio, or candid moments and what the offices looked like. I didn’t have any use for those photos back then, but now they are essential to the whole fan book experience. For example, there’s one shot of a whiteboard with a countdown of how many days left there are before the completion of the very first LCD album.

Can you speak to the time period when these photos were taken?

The DFA label and other bands — The Yeah Yeahs, The Strokes — come out of a post-9/11 reality. After 9/11 there were a few years when I thought New York was kind of done. There was a sad feeling in the air, it was a tough thing to move on from. It was really catastrophic. These bands had to create something in that space and it ended up being a scene that, no matter how you look at it, was born in the shadow of 9/11. My buddy Mike wrote about it in the forward to the book.

The Juan Maclean, rooftop of Plantain Studios, 2003 (Tim Soter)

What do you think has changed regarding live shows in New York?

Information is more democratic now. Nearly everyone has the same access to knowing everything that’s going on, because of TikTok and Instagram. Whereas back then, it was a little more niche. And also more accessible. Because real estate was cheaper, there were so many more independent music venues. I also don’t think there’s one photo in the book of anyone with a phone in their hand. People seemed to be in the moment.

What is the current state of the kind of fan photo book you set out to create?

Bands used to have these big glossy tour books full of information, but the current ones I’ve found are different. Not long ago, I went on Amazon and typed in “Travis Scott,” since he’s huge right now. I found two Travis Scott fan books, a joke book and a photo book. But the passages seemed a little off, like they were partially written with AI. Two weeks later, I checked back and both books were taken down. What I find interesting is that information is now so widespread via the internet that anyone can create their own fan book if they really wanted to.

Gear at Plantain Studios, May 15 2003 (Tim Soter)

The post ‘For ones who were there’: A new photo book charts the origins of DFA Records appeared first on Brooklyn Magazine.