LIDAR Discovers Mysterious Maya Underground Chamber In The Rainforest

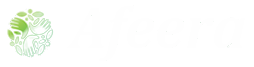

Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – A LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) survey conducted in Campeche, Mexico, has revealed significant archaeological findings. The survey covered an area of 140 square kilometers, penetrating dense vegetation and uncovered a previously unknown outpost, now named Ocomtún, which translates to “Stone Pillar.”

Surrounding Ocomtún, researchers identified several ceremonial sites. These satellite structures were the focus of an expedition earlier this year. During the analysis of photographs from the expedition, scientists observed an unusual structure that was later determined to be an underground chamber within a Mayan compound located deep in the Mexican rainforest.

Central part of the site where the drainage tunnel was found. Credit: INAH

The underground chamber was hidden beneath Bone of the Mayan ritual ball courts. It appears that the ballpark was built on top of the ruins of another building. The archaeologists do not yet know the what the underground chamber was used for but there it no doubt it was important.

This discovery is particularly noteworthy as it provides insight into human behavior in the region long after the collapse of the Mayan civilization. The presence of this chamber suggests that some populations continued to inhabit the area for hundreds of years following the decline of the broader Mayan culture.

“We have found several ancient Maya settlements, with remains of residential buildings and temple pyramids,” said Dr Ivan Šprajc, who led the expedition on behalf of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History.

Dr. Šprajc’s research shows that lower regions lack terraced fields and canals. Settlements there are small with few significant structures. Walls and architectural decorations are rare, and monuments are few, small, and unadorned. Preliminary ceramic analysis suggests peak occupation during the Late and Terminal Classic periods (600-1000 AD). This may result from late-stage migrations, possibly due to population growth in nearby, more suitable areas.

View along the tunnel. Photo: Vitan Vujanovic.

“The inevitable impression is that the Mayan culture of this region we have just explored was noticeably less elaborate than that of Petén to the south, and the regions of Chenes and Chactún to the north and east,” he said.

Outside the complex, near its northeast corner, researchers also observed a channel draining water from the plaza. This feature was associated with an early stage of development and later covered during renovations. Dr. Šprajc notes that they also inspected another site this season. The eastern sector featured a ball game court, where they discovered a substructure possibly dating to the Early Classic period (200-600 A.D.), covered with painted stucco remains.

Part of the ball court substructure found in the test pit. Photo: Octavio Esparza Olguín.

The INAH team identified an additional site with structures concentrated on a natural elevation and a rectangular water reservoir. Its main plaza boasts a 16-meter-high pyramid, atop which they found an offering containing ceramic remains, a fragment resembling an animal leg (possibly a tepezcuintle or armadillo), and a bifacial flint point.

See also: More Archaeology News

The archaeologist concludes that this material, likely from the Late Postclassic period (1250-1524 AD), indicates human presence in the centuries before Spanish arrival. This occupation occurred long after the Central Lowlands experienced the disintegration of complex political entities and drastic population decline towards the end of the Classic period (200-600 AD).

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer